Being Confronted by Cambodia’s Painful Past

Throughout the course of history, people have done horrible things to other people.

We have invaded, pillaged, destroyed, and claimed other lands. We have raped, tortured, enslaved, and killed other people. For as long as we have been on the earth, humans have been doing terrible things to one another. No country or race or class is innocent if you look back in the history books.

But it's one thing to read about the unspeakable cruelty humans are capable of in books.

It's another entirely to be confronted by it face to face.

It's an eerie feeling, walking over graves. Cemeteries always sort of creep me out because of that.

But the feeling changes to abject horror and disgust when the graves turn into mass graves, and you begin to learn about how people came to find themselves in them.

Before my trip to Cambodia, I knew a little bit about Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge and the genocide and associated starvation that claimed the lives of roughly 3 million people between the years of 1975 and 1979. But simply knowing that more than 1/3 of Cambodia's population died in the span of 4 years didn't mean I was prepared to be confronted by it.

Genocide is never a comfortable topic; never something that we WANT to be confronted by. But, sometimes I think we need to be.

And a visit to the Killing Fields at Choeung Ek is certainly confronting.

During the reign of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, upwards of 20,000 people lost their lives at this site alone. At one time, Choeung Ek was a quiet Chinese cemetery. Today, it is a reminder of the harsh reality of genocide.

Throughout Cambodia, there are at least 343 of these “killing fields.” Some were actual fields. Others were caves or orchards or riverbanks — anything out of the way that would make a suitable site for systematic slaughter.

Ol' Pol Pot was a messed up ruler — as most rulers who incite genocide tend to be. He was so obsessed with the idea that his people would revolt against him that he decided getting rid of them was a better option than letting them potentially decide they would be better off without him. Over the span of 4 years, the Khmer Rouge gathered up millions of people — usually educated ones — and sent them to “New Houses” or “Training Centers.”

These of course were just code names for killing fields or facilities where the people would be beaten to death or near-death with iron bars or wooden clubs (because their lives were not worth the cost of bullets) and then shoved into mass graves. Some of them were still alive when they were thrown in.

Women would watch their babies be beaten against trees, and then would be raped to within inches of their lives before being thrown into the pits, too.

All because one man was afraid of his own people.

Our guide for the day — who lived through this horror — explained how the “educated” people were tracked down. Doctors, teachers, lawyers and anyone in a profession that obviously required an education were the first people targeted. Then it was people who wore glasses (since they could probably read), people who spoke more than one language, and people who had smooth hands or pale skin (since they probably didn't work out in the fields). If that sounds crazy to you, it's because it was.

Roughly 1.5 million people were sentenced to death this way.

But millions more died of starvation during the same period. Along with hunting down educated people, the Khmer Rouge emptied cities and sent people to work in the fields at glorified slave labor camps. There was never enough food, and people suffered an incredible amount. Our guide lost his father as well as 3 siblings to starvation during the reign of the Khmer Rouge, and remembers eating everything from bugs to dirt in order to stay alive.

The true horror? Most Cambodians over the age of 40 alive today can tell similar stories.

Walking through Choeung Ek was like walking through a nightmare. Sure, it was sunny. But then our guide would point out bones poking up out of the dirt, or perhaps a few human teeth just lying in the grass. Each time it rains here, more things — bones, teeth, bits of clothing — are exposed. There are piles of these things everywhere, like grotesque memorials to the dead.

And then there's the gigantic, ornate stupa, filled with the bones of about 8,000 people whose bodies were exhumed from mass graves at this site a few decades ago. So many bones. So many lives lost for no good reason.

The bodies still in the earth at this particular killing field are mostly those of political prisoners, many of which were held at the Tuol Sleng prison and detention center in Phnom Penh.

This prison — along with many others like it — were known as “Re-education Centers” during the Khmer Rouge era. Really, though, they were just torture facilities. Prisoners (AKA suspected educated people) would be kept here in appalling conditions and interrogated regularly. The goal? To get them to name names — their family members, people they worked with, etc. Their captors would promise their release and a new life at a “New House” if they talked. Of course, once they did (or if they didn't), they were just sent to the killing fields.

Visiting Tuol Sleng (which literally translates to the “poison hill”) was no less confronting than visiting the killing fields. It was important, though, to understanding how the genocide was carried out — and how the aftermath still affects people in Cambodia today.

At Tuol Sleng, two thin and bent old men can often be found selling books — autobiographies — that describe their time at Tuol Sleng and how they were able to survive. These men are given nothing by the government; after being tortured and starved for years, they now rely on visitors taking pity on them to make a living.

It's just one hint at the state of Cambodia's current political landscape that our guide pointed out to us. He also pointed out that, even though Pol Pot was eventually chased from power, many Khmer Rouge soldiers and officers still hold positions in Cambodia's government today. Add to this the fact that an entire generation of educated people (not to mention their families) was wiped out, and it makes for a fairly scary state of affairs today in Cambodia.

As we entered Tuol Sleng, our guide told us that we could ask questions during the tour, but instructed us to refrain from asking anything about politics.

“There are ears in the walls here,” he said.

We all learn about the Holocaust in school; about how horrible and evil it was. But I don't remember learning nearly as much about the Cambodian genocide. By all accounts, it was just as brutal as the Holocaust; millions of people were put to death on orders from one crazy man. A whole generation was wiped out. And it happened more recently than WWII — so recently that there are still many survivors of the Khmer Rouge years alive in Cambodia today.

So why don't more people know about it?

The answer, of course, is complex. For starters, the U.S. actually supported Pol Pot for quite a long time because, even though he was crazy and there were rumors that he was committing terrible crimes against his own people, he was very anti-Vietnam. And this was at a time when the U.S. was fighting a war with Vietnam and looking for allies.

It's disgusting, really, to think that genocide could ever be supported. But it's actually happened more times than most people realize.

And it will probably continue to happen unless we educate ourselves better.

Visits to places like the Killing Fields and Tuol Sleng are not pleasant; being confronted by this type of human cruelty is never a comfortable thing. But I think it's SO important to be aware of why and how and when this happened, so that we might be able to open our eyes to similar things happening in the future and speak up about them.

Educate yourself, even if it means subjecting yourself to uncomfortable truths every once in a while.

Heading to Phnom Penh and interested in visiting these sites to learn more about them? Consider booking a tour with a company like Urban Adventures. Their Phnom Penh's Past tour is essentially what I wrote about here.

Would you visit “dark” places like this in Cambodia?

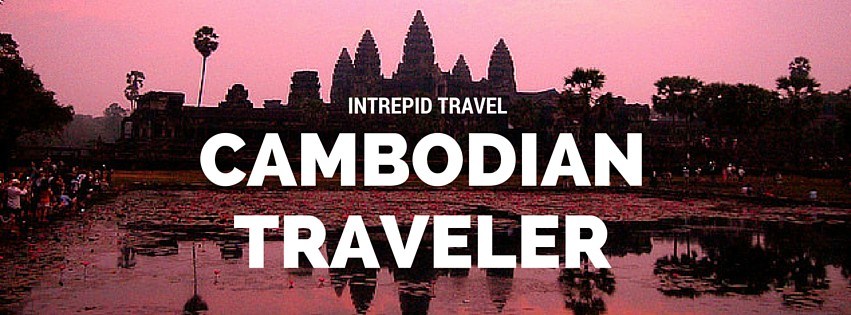

*Note: I visited these sites as part of a complimentary tour of Vietnam and Cambodia with Intrepid Travel. I am SO glad that this half-day tour was included during our time in Cambodia, because you really can't understand Cambodia without visiting these places, sad and disturbing as they are.

If you're interested in the Cambodia portion of this same trip, check it out here.

Amanda Williams is the award-winning blogger behind A Dangerous Business Travel Blog. She has traveled to more than 60 countries on 6 continents from her home base in Ohio, specializing in experiential and thoughtful travel through the US, Europe, and rest of the world. Amanda only shares tips based on her personal experiences and places she's actually traveled!

I think noir tourism is as important as any other type of tourism — perhaps even more so, for the simple reason that we must educate ourselves. Reading about genocides and tragedy in school, to me, always felt like I was reading a historical novel, as if it were too tragic to be true. But actually setting foot in the places where these dramas happened takes a whole new meaning, and it changed me forever. These are essential experiences when travel is concerned.

I absolutely agree. Simply reading about these things, it’s easy to distance yourself from them. But when you’re actually THERE, where these heinous things happened? It makes it much more real and tangible.

I feel like the Killing Fields are a place you HAVE to see if you’re in Cambodia, if only to honor those that were killed.

I agree!

Very well said Amanda, it couldn’t have been easy to write about this. My heart aches just thinking about the atrocities that happened in Cambodia. It shocks me that things like this can happen. As hard as it is, i feel its important we confront ourselves with things like this when travelling to help ensure they stop happening.

It definitely was not easy, but, yes, important I think – both for me to have seen this, and to write about it. I’ll admit that I didn’t love Cambodia; the country faces a LOT of issues right now, and likely will continue to face them in the future. And a lot of those issues wouldn’t exist if not for this history. So it’s really important to understand it in order to better understand Cambodia.

I always found it a bit weird that people would actually pay money to visit sites where massacres took place but after witnessing the Killing Field’s memorial in Siem Reap I can understand why this is a very important matter: By remembering the past we can make sure that it will never happen again in the future.

That’s exactly it, Raphael!

You’re great at writing these posts Amanda. You know to capture so much in a relatively short post and you really get through to each time.

I absolutely agree with you that education is key and most importantly I think that we should educate ourselves and our children. Not let the school educate them, educate them ourselves.

Why? Because, unfortunately, school programs are often imposed or need to be approved by the government and we all know that governments aren’t exactly the most objective parties in these kinds of things.

It appalls me how often governments can’t even apologize for actions of their predecessors or set things straight. No, they weren’t the ones who actually submitted the crimes or let them happen, but they are the ones who can try and set things right again.

Thanks so much, Sofie. I know I don’t tend to write really heavy posts on my blog often (though it certainly has felt like I’ve written more of them recently!), but it’s good to hear that the message comes though when I do.

Education can go beyond yourself and your family, too – even telling friends and coworkers about places like this you’ve visited on your travels can often open up interesting discussions.

I fully agree. I just emphasized children because I think a lot of people expect schools to educate their children on such subjects.

I definitely agree with you on that one.

Ah, Amanda. I’ve always struggled with this dilemma. In places where such horrific things happened (i.e. Germany, Poland, Cambodia, and many other), would I be able to bring myself to confront them head on? I honestly don’t know. I realize how important it is to educate ourselves and to not let these things be forgotten, but at the same time, I really don’t think I can go through the memorials without my heart hurting and tears streaming down my face (heck, it’s happening now as I read this post).

I totally understand, Pauline. There were some women in my tour group who didn’t want to go to the Killing Fields for that reason. But, in my mind, me being sad for one day in no way matches up to what the victims suffered. I feel like I owe it to them to at least confront the reality, even if it hurts. I convinced those couple of women to come with us, and although they admitted that it was very hard to see, they were glad they went in the end. It’s such a big part of Cambodia’s history – such a big influence in why Cambodia is the way it is today – that I would tell you to make yourself go!

Fabulous post, as always. It really is appalling how little we learn about non-western history in school. While the holocaust is obviously horrifying, it is one of many, many genocides and tragedies, and by no means the most recent. When I lived in Argentina I went to the Museo de Los Desaparecidos and it was a very difficult experience to realize that people affected by this were either my parents age or my age. Basically, the argentine military regime kidnapped and murdered thousands of young people in the 1970s and if the women were pregnant or had small children they gave the children away to military families. So, many people just 10 years older than me are suddenly finding out that their parents aren’t their parents. It’s horrific. While I was at the museum, this woman, who could have been my age, ran out crying and screaming. I don’t know what her story was, but it really affected me.

Not saying that it’s “better” in other countries, but I definitely take issue with the fact that in U.S. schools we pretty much only learn about U.S. history and ignore everything else. Part of the reason I’m drawn to travel is the chance to learn about all the history that the U.S. didn’t think was important enough for me to learn about.

This was a very sobering piece to read and can only imagine the feelings of emotions circulating through you when visiting these dark places.

The fact that these atrocious acts were committed rather recently makes them all the more devastating. I don’t know a lot about this era but know that so many of those responsible were never prosecuted for their crimes which I can’t even imagine.

I would like to visit places such as these because I agree with you that doing so is of the utmost importance and also lets the victims and survivors know that the acts will never be forgotten.

Yes, many members of Pol Pot’s inner circle have never been charged for their crimes – many of them still enjoy lives of relative luxury in Cambodia, even though their neighbors usually know who they are and what they’ve done. It boggles my mind! But, sadly, that’s Cambodia.

I agree, it’s important to remember these atrocities. I didn’t visit Cambodia, but did visit the concentration camps in Germany. Entering these places messes with so many deep feelings…

Definitely, Yara. These aren’t places I would ever visit for a second time, but I think that first visit was important.

Well written and described! It was funny to notice how my take on visiting places like this changed while reading your post. My first idea after seeing the headline was that “oh yeah, I want to visit that too one day”. But when I read on to babies being beaten I started to think that I dont want to expose myself to this kind of experience. The feeling stayed until I got towards the end of the article, I think your line about educating ourselves despite it being “uncomfortable” is important.

Thinking back, one of my most powerful travel memories after 25 countries is when I visited the West Bank in the Occupied Palestinian territories. It was not a cheerful place either, but I felt like I really learnt something, had an eye opening experience there.

For me, these learning experiences are one of the reasons why I travel. I mean, of course I love to go to the beach and take touristy photos and have a good time. But places like these… these are the ones that really stick with me.

Thanks for sharing your thought process and how it changed as you read the post!

I visited these places while I was in Phnom Penh as well. I thought both Choueng Ek and Tuol Sleng both provided excellent documentation of the history in solid English translations. While I was in Taipei, I visited the 2-28 Museum, which recounts then 2-28 Massacre. I felt like they could have done a better job interpreting the exhibits for foreign tourists. Places like these are horrific, but important for all of humanity to see so that hopefully things like this never happen again.

Yes, these places definitely serve a purpose. But your point about interpretation is really important – without good interpretation, the message can often be lost or miscommunicated.

Very powerful read, thank for sharing, Amanda! You’re right — why do we not learn about this in school? (Other than the reasons you pointed out, of course). It’s so important to educate yourself. My husband and I visited Auschwitz and Auschwitz-Birkenau when we were in Poland, and my feelings about visiting were just like yours. It was not an enjoyable day, but a necessary day. Necessary to confront and learn about what had only been stories up until that point for me. I also viewed it as a way to pay homage to those lost. A guide told us that the survivors asked that the camps not be torn down after WWII was over so that others, in the future, could come and learn about the atrocities committed. And learn we must!

Auschwitz was similarly very difficult for me, even though I was much more familiar with what had happened there. But yes, even though some people view the preservation of these sites as a bit macabre, I’m glad that they still exist. It’s important to confront these sorts of realities sometimes.

I agree, that these visits are important. But sometimes, there is only so much a heart can take. In the last year, like you, we’ve seen these spots, Auschwitz, watched as protesters were shot at in Phnom Penh, and then endured the heartache of watching our beloved Turkey go through so many troubles. We need a break from such visits for awhile.

I totally understand, Dalene. It’s definitely not easy to see so much suffering in such a short period of time.

I too visited the places above and was horrified. Flying into Cambodia I sat beside a gentleman who lost his entire family in the genocide (he now lives in the U.S.) – his father was a teacher at the school which became a prison pictured above so he was one of the first ones assassinated in Phnom Penh along with his wife and children. My seat partner was spared because he was ten years old – the right age to become a child soldier. (and spy) I didn’t even want to know about that part of his life. I knew Cambodia was going to be a very emotional place to visit before we even touched down on the tarmac. I don’t regret visiting however even though it was very painful and upsetting. I did buy one of the autobiographies (by Chum Mey)sold there and it was a very troubling read.

It just boggles my mind to think that MOST people over the age of 40 in Cambodia today have stories like that to tell… It’s very sobering.

Thanks for writing about what my wife and I can expect when we visit in a month or so from now. I can’t wait to visit and learn, but at the same time it’s going to be a tough day. We also have a 2-year old boy with us and, having never been there and not knowing what to expect. I’m not sure if he should come or not. What do you think? Is it appropriate?

I’m really glad to hear that places like this are part of your itinerary, Chris.

As for taking a 2-year-old… I don’t think there are any rules against it, but I’m also quite sure that he wouldn’t understand what he was seeing. It really depends on whether you think looking after a little one would take away from your own experience. These are both very heavy places. I don’t know if I would recommend taking very young children – but then again I’m not a parent!